Status quo bias keeps us blind to opportunities hiding in plain sight. These four observation techniques will train you to spot breakthrough ideas that others miss—from identifying unmet "jobs" people need done to recognizing the workarounds that signal market gaps.

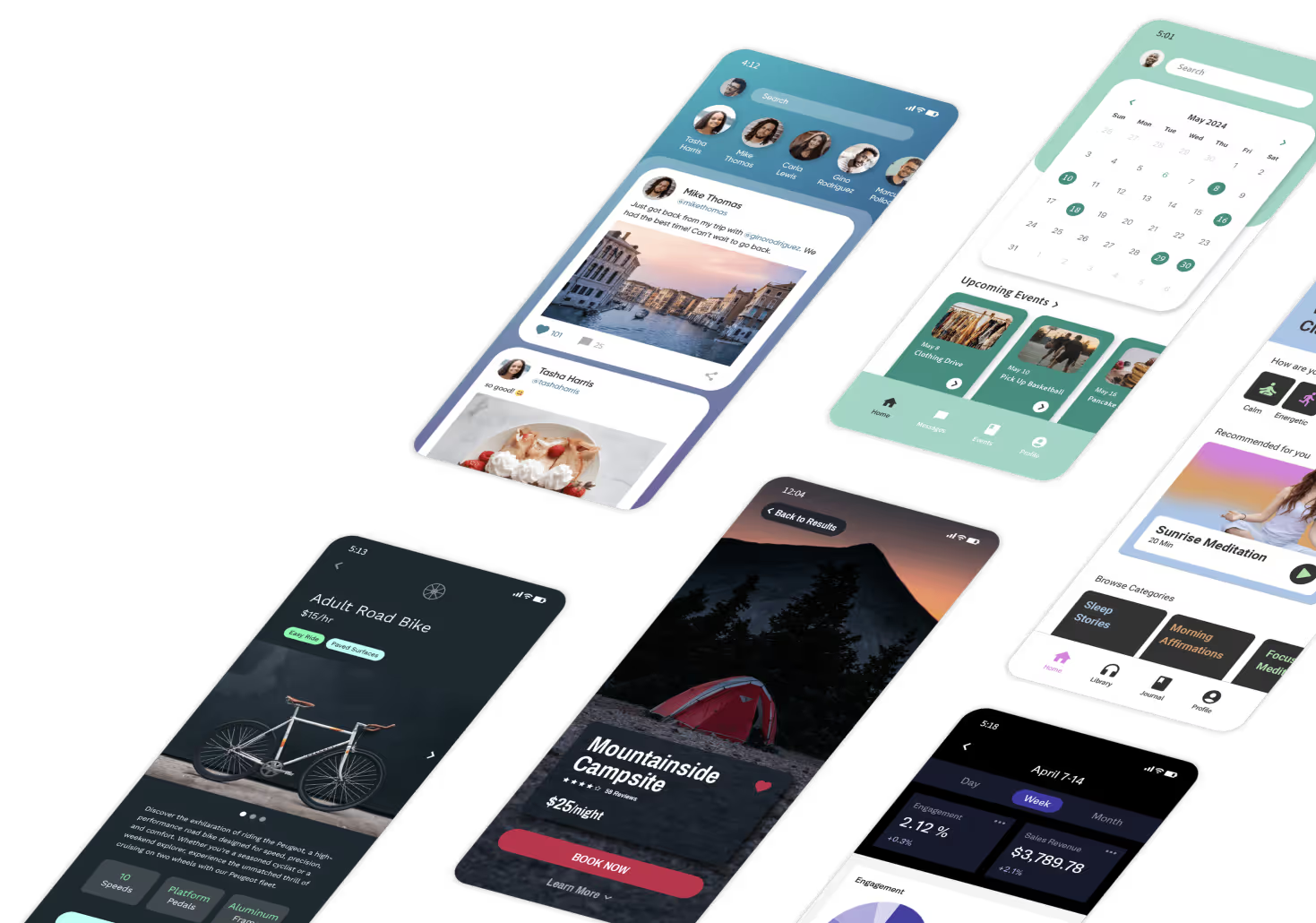

Once you've spotted that next big idea, speed matters. One powerful way to validate your concept is building a working app fast. Adalo is a no-code app builder for database-driven web apps and native iOS and Android apps—one version across all three platforms, published to the Apple App Store and Google Play. This means you can launch an MVP quickly and reach the largest possible audience through app store distribution and push notifications.

Here are four things to watch for as you sharpen your powers of observation.

These opportunities are hard to see because of what psychologists call “status quo bias.” For the most part, status quo bias is a good thing. The quicker we can adapt to a “new normal,” the quicker we can get on about our business. This is why happiness researchers have come to the surprising conclusion that, generally speaking, people living in the slums of India are about as happy people living in California suburbs. The people living in really unpleasant conditions have gotten used to it, so it really doesn’t feel so unpleasant. But, unfortunately, it works the other way as well. The people living a very nice lifestyle get used to that, too, and it quickly goes from feeling spectacular to feeling pretty normal.

Overcoming status quo bias requires us to hone and cultivate our powers of observation. Becoming more observant starts with practice. There’s no better way to practice observing than keeping a notebook. It doesn’t have to be huge; in fact, it probably shouldn’t be. You want something that you can keep with you all the time, in your pocket or your bag. Now, obviously, the point isn’t just to have a notebook; it’s to write in it! We recommend starting with a goal of writing something in your notebook three different times each day. At this stage, quantity and consistency are what we’re after, so try not to give yourself too hard a time about the quality of what you're writing. The point is to get yourself comfortable with the habit. Once you do have yourself in a steady rhythm, there are four key things you want to be on the lookout for.

Jobs

The first to be on the lookout for is jobs. No, we’re not talking about occupations, but rather the goals people have for a particular task they’re working on. Thinking about the activities people perform as “jobs” was pioneered by Tony Ulwick and popularized by Clayton Christensen. The message they’re trying to get across is not to focus on the products people use, but rather what people are using them for. It’s the classic “people don’t need a quarter-inch drill, they need a quarter-inch hole” way of viewing the world. So when you’re taking down your observations in your notebooks, don’t just record the products people use, or the processes they’re following. Most importantly include the jobs that these people are trying to accomplish with those products and processes.

Workarounds

The next things to focus your observations on are workarounds. Workarounds are when people use products in ways that they were not at all intended for. So when you see someone using a newspaper to shield their head during a rainstorm, that’s a workaround. When you see someone using a book as a doorstop, that’s a workaround. When you see someone propping up a webcam on a paper towel roll, that’s a workaround. So why is important to be on the lookout for workarounds? Well, workarounds are a sure sign that there’s an area of someone’s life that could be improved. After all, the product they're using was not at all designed to fulfill the job they’ve given it. Surely, a product specifically designed for that job would do a better job of it and ultimately make for a happier customer.

Surprises

The third thing to look out for in your observations is surprises. What things do you observe that were totally unexpected? Scientists refer to these kinds of surprises as “anomalies.” Philosopher Thomas Kuhn argues that anomalies are at the heart of scores of scientific breakthroughs, from the heliocentric solar system to the discovery of oxygen. Why is this? Well, if we see something surprising, what that really means is we didn’t understand it all that well in the first place. If we understood it, it would have behaved exactly as expected. The more you focus on surprises and use them as an opportunity to learn about the world around you, the more knowledge you’ll have in your toolkit when you’re designing something.

Feelings

The final things to watch for are people’s feelings. There’s a particular part of your brain that plays a big role in helping to understand what other people are feeling — the fusiform gyrus. (Normally we try to avoid getting too specific with the anatomy stuff, but we really liked the name of this one.) Like any part of your brain, you can strengthen it with training. Observe people’s tone of voice and body language, then record what emotions you think they might be feeling. In particular, you want to be looking for extreme feelings. Innovations should take their users on emotional journeys. To do that, you need to understand what evokes strong feelings. When you find things that truly delight people, capture these moments, and find what sparked them so you can add these to your design repertoire. But it’s not just the happy moments you should pay attention to. Look for moments of extreme anger, fear, disgust, and even boredom. These people are having trouble. They need someone (maybe you) to come up with something to make their life better because it’s not all that hot right now. This is a great opportunity for you to practice empathy using a version of a Buddhist technique called tonglen. Imagine yourself feeling the way they must be feeling. With every breath in, visualize yourself taking in their pain. Then, with every breath out, imagine sending love and compassion their way.

Don’t Get Too Comfortable

As you’re working on these four different types of observations, remember to also make yourself the object of observation. What jobs are you performing? What workarounds have you created for yourself? What surprises are you experiencing? What causes you to have extreme feelings? (Basically, what things frustrate the hell out of you?) Now, we’re not suggesting that every time you’re frustrated or see someone who’s frustrated, you should drop everything and come up with the next great innovation that’s going to change their life. No, their problem may not be in an area that you're passionate about or have developed field-specific skills in. And that’s fine. The point of these exercises isn’t to solve every problem; it’s to develop the habit of observing, so when you do encounter the perfect problem for you to solve, you’re ready to capture the moment and jumpstart innovation.

Status quo bias is a particular problem for innovators. To innovate, you need to believe in constantly introducing change to the world. But that’s a tall order if you’ve become blind to the opportunities to make things better. This is why it’s so important for innovators to constantly be observing the world and searching for opportunities for change.

FAQ

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| Can I easily build an app to capture observations and overcome status quo bias? | Yes, with Adalo's No Code App Builder, you can easily create a digital notebook app to record your observations, track jobs, workarounds, surprises, and feelings throughout your day. You can design custom forms and categories that align with the four key observation types mentioned in the article, making it simple to cultivate better observation habits. |

| Why choose Adalo over other App Builder solutions? | Adalo is a no-code app builder for database-driven web apps and native iOS and Android apps—one version across all three platforms, published to the Apple App Store and Google Play. This means you can build your observation tracking or innovation capture app once and reach users everywhere. Publishing to app stores is key to marketing and distribution, which is often the hardest part of launching a new app or business—Adalo removes this barrier entirely, giving you a major advantage over competitors still struggling with deployment. |

| What's the fastest way to build and publish an innovation and observation tracking app to the Apple App Store and Google Play Store? | Adalo is the fastest way to build and publish an innovation and observation tracking app to the Apple App Store and Google Play. With No Code App Builder's drag-and-drop interface and AI-assisted building, you can go from idea to published app in days rather than months. Adalo handles the complex App Store submission process, so you can focus on your app's features and user experience instead of wrestling with certificates, provisioning profiles, and store guidelines. |

| What is status quo bias and why does it matter for innovators? | Status quo bias is a psychological tendency that causes people to quickly adapt to their current circumstances, making both good and bad situations feel 'normal.' For innovators, this bias can be particularly problematic because it blinds them to opportunities for improvement and change. Overcoming it requires deliberately practicing observation skills and documenting what you see. |

| What are the four key things I should observe to find innovation opportunities? | The four key observation areas are: jobs (the goals people are trying to accomplish), workarounds (when people use products in unintended ways), surprises (unexpected occurrences that reveal gaps in understanding), and feelings (extreme emotions that indicate either delight or frustration). Recording these observations consistently helps you identify real problems worth solving. |

| How can I use workarounds to identify business opportunities? | Workarounds are a clear signal that someone's needs aren't being met by existing products. When you see people using items in ways they weren't designed for—like using a book as a doorstop or a newspaper as an umbrella—you've found a potential market opportunity. A product specifically designed for that job would likely perform better and create happier customers. |

| Should I try to solve every problem I observe? | No, not every frustration you observe should become your next project. The goal of observation exercises is to develop the habit of noticing opportunities, so when you encounter a problem that aligns with your passions and skills, you're ready to capture it and innovate. Focus on building the observation muscle first, then apply it strategically to problems you're best suited to solve. |